Contact to me

Contact to me

I was in pursuit of a top-tier driver without compromises, significant dimensions and weight did not deter me and I embraced the challenge of crafting a fitting chassis for it

That is why I chose this material

For these headphones, I never considered using any material other than genuine metal. While some modern resins offer excellent structural rigidity, I chose to construct the headphones entirely out of metal, even for components where metal wouldn’t have had a direct functional advantage. Simply put, I didn’t want a single square millimeter of plastic on these headphones. I could have used magnesium, but after a careful cost-benefit analysis, I opted for premium 6061 aluminum, milled from solid and anodized. This is a well-established choice in high-end headphones, and I didn’t invent anything new—rather, I used what was technically appropriate to ensure maximum torsional rigidity: metal. A very hard wood could have been an option, but I sought harmony among the various components, and building the headband mounts out of wood would have been a mistake. At that point, it would have been better to make them out of plastic and settle for compromises. Why should I have done that? Metal, please!

Among the possible metals, the choice came down to titanium, magnesium, and high-quality aluminum. I ruled out titanium due to its excessive specific weight and dismissed magnesium, despite being the lightest metal, because it didn’t prove advantageous in my cost-benefit evaluation. In the end, 6061 aluminum won the selection.

I am not a sound engineer, nor do I have specific expertise in tuning a driver. My priority is to build with purpose and understanding, trusting that quality craftsmanship always leads to a quality result

acoustic chamber

acoustic chamberThe diaphragm utilizes every available inch within the driver frame, and the large driver takes full advantage of the space within the ear cup diameter. Consequently, it would have been impossible to secure a pad while keeping it within the cup’s diameter without obstructing a significant 15% of the diaphragm, effectively wasting precious sound quality in a very literal sense. This was the primary reason I designed a 4mm rise to create a noticeable separation between the sound-producing surface and the pad. The result of this experiment is twofold: not only has it fully unleashed the potential of the driver, but it has also allowed me to create a reasonably sized acoustic chamber that significantly broadens the soundstage, enabling the various instruments to express themselves to their fullest potential

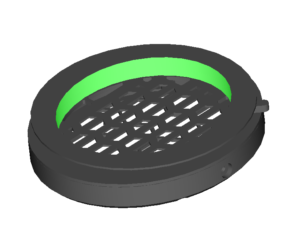

ventilation openings

ventilation openingsThe availability of a 4mm thickness allowed me to incorporate ventilation holes, facilitating appropriate airflow and the exchange of clean air within the acoustic chamber. This design advantage enables long listening sessions without straining our eardrums or causing our brains to plead for a break, as they simply won’t require one

freedom of choice

freedom of choiceAlongside proper ventilation, there is an additional acoustic advantage: it further expands the soundstage and brings vocals to the forefront, albeit at the expense of a slight reduction in bass response. However, any loss of detail is compensated by an even more pronounced separation of the instruments

adjustment possibilities

adjustment possibilitiesNothing is predetermined. A knob positioned just behind the pad allows for customizable adjustment of the ventilation openings, enabling partial or full exposure, all the way to complete closure. I have found that opening only the first ventilation hole serves me well, but any adjustment is not only possible but advisable for extended listening sessions

I experimented with various pads and ultimately settled on what I thought was the best option. To be honest, I chose the least unsatisfactory one. I believe the pad can be improved, and I have crafted some prototypes using acoustic material for the padding, which yielded results I found quite pleasing. Thus, I could and should have made the pads myself, but I simply don’t know how to sew, and I couldn’t find a tailor willing to create them to my specifications. In the small town where I live, even simple tasks can seem impossible. I will have the time and opportunity to enhance this final aspect of the headphones, which is why I opted for an extremely simple pad attachment mechanism, allowing for experimentation with different solutions

I wanted some stable cups

In the first pair of headphones I created, I used a knob that, when tightened, allowed me to secure the vertical position of the ear cup. In this iteration, I aimed to improve upon that aspect by designing a system that employs a small metal piston located within the mounting plate of the headband. This system features a spherical end that, when pressed against a custom-machined notched pin, creates a closely spaced ‘click’ mechanism. A simple push on the pin or a deliberate pull of the cups is sufficient to select the click corresponding to the desired height, and once set, it remains fixed until further adjustment.

In the first pair of headphones I created, I used a knob that, when tightened, allowed me to secure the vertical position of the ear cup. In this iteration, I aimed to improve upon that aspect by designing a system that employs a small metal piston located within the mounting plate of the headband. This system features a spherical end that, when pressed against a custom-machined notched pin, creates a closely spaced ‘click’ mechanism. A simple push on the pin or a deliberate pull of the cups is sufficient to select the click corresponding to the desired height, and once set, it remains fixed until further adjustment.

I also designed a small hole through which a pressure adjustment knob can be inserted to select the appropriate pressure for the piston. I opted not to fix this knob in place, as I felt it would disrupt the aesthetic; it is an adjustment likely to be made infrequently. I deemed it unnecessary to add weight to the already considerable design of the headphones by keeping this adjustment mechanism readily available

Achieving the perfect clamp on the temples is a challenge I believe I have mastered

Designing a headband presents easily understandable challenges. It requires achieving the correct clamp on the temples by using the right curvature and material. Aluminum would not have performed this task adequately, and I also wanted the pressure on the temples to be adaptive, allowing the user to choose and adjust it based on the shape of their head. I dismissed carbon fiber from the start, as its lightweight nature wouldn’t allow for precise regulation of pressure on the temples. The final choice fell on 304 stainless steel, a material known for its ‘shape memory,’ which enables the user to precisely mold the headband to their needs. This type of steel is ideal for audiophiles because, once the perfect shape is achieved, it retains a certain flexibility, allowing the headphones to be easily worn while returning to the exact shape and providing the desired clamp. This requires the end user to manually and personally adjust the headband, but I see this not as a drawback, but rather as a virtue. Those who have used this headband swear it is one of the most comfortable and stable they’ve ever experienced, and their feedback leads me to believe that I’ve succeeded in providing both stability and comfort to headphones that are neither light nor easy to balance

Designing a headband presents easily understandable challenges. It requires achieving the correct clamp on the temples by using the right curvature and material. Aluminum would not have performed this task adequately, and I also wanted the pressure on the temples to be adaptive, allowing the user to choose and adjust it based on the shape of their head. I dismissed carbon fiber from the start, as its lightweight nature wouldn’t allow for precise regulation of pressure on the temples. The final choice fell on 304 stainless steel, a material known for its ‘shape memory,’ which enables the user to precisely mold the headband to their needs. This type of steel is ideal for audiophiles because, once the perfect shape is achieved, it retains a certain flexibility, allowing the headphones to be easily worn while returning to the exact shape and providing the desired clamp. This requires the end user to manually and personally adjust the headband, but I see this not as a drawback, but rather as a virtue. Those who have used this headband swear it is one of the most comfortable and stable they’ve ever experienced, and their feedback leads me to believe that I’ve succeeded in providing both stability and comfort to headphones that are neither light nor easy to balance

I chose to dedicate no less than 50 grams to comfort and refinement

Just like the clamp by headband, the band plays a crucial role in fully enjoying your music. It is responsible for distributing the considerable weight of the headphones. To ensure even weight distribution, I designed the band to be positioned at the ideal height, and to avoid limiting this choice, I created slots at the selected height where the band can be secured. Once again, I did not allow weight savings to dictate my approach, focusing solely on functionality to offer the utmost comfort. I crafted the band with a triple-layer design: the lower layer, which rests against the head, is made of genuine Alcantara—a prestigious Italian material renowned for its comfort against the skin, probably the best available. The upper layer is genuine leather, and the middle layer is memory foam. This combination approaches, and in some cases exceeds, 50 grams, nearly 10% of the total headphone weight. However, I have concluded that the benefits it provides in terms of comfort and refinement far outweigh this slight increase

Just like the clamp by headband, the band plays a crucial role in fully enjoying your music. It is responsible for distributing the considerable weight of the headphones. To ensure even weight distribution, I designed the band to be positioned at the ideal height, and to avoid limiting this choice, I created slots at the selected height where the band can be secured. Once again, I did not allow weight savings to dictate my approach, focusing solely on functionality to offer the utmost comfort. I crafted the band with a triple-layer design: the lower layer, which rests against the head, is made of genuine Alcantara—a prestigious Italian material renowned for its comfort against the skin, probably the best available. The upper layer is genuine leather, and the middle layer is memory foam. This combination approaches, and in some cases exceeds, 50 grams, nearly 10% of the total headphone weight. However, I have concluded that the benefits it provides in terms of comfort and refinement far outweigh this slight increase

I wanted a headset that contained harmonious edges

I have a deep appreciation for beauty, but I don’t consider myself a capable designer. When I work on a project, I let the end goal guide me, allowing ideas to form along the way. In this case, however, I placed my complete trust in the aesthetic expertise of my friend Benny, who gave me the initial creative direction. Despite some deviations, where his taste clashed with functionality, I managed to preserve the original concept. The honeycomb grille and the exposed bolts were his ideas—both perfectly suited for the design. Leaving the bolts visible allowed me to develop the best possible solution for anchoring the driver. I needed precisely that type of bolting to keep the cup’s size within acceptable limits; I feared exceeding 120 mm in diameter but managed to contain it within 105 mm at the smaller end and 113 mm at the larger.While the original design sketched circular ear cups, the project’s evolution demanded oval ones, which we didn’t want. I compromised by subtly ovalizing the circle just enough to serve the design’s effectiveness. The result was fully approved by my friends who supported me, and I take this opportunity to thank Benny, Valentino, Mauro, and Achille for their financial contributions that lowered the production cost. My great reward lies in delivering them a high-end headphone, capable of competing with top-tier models, at actual production cost. As I write, it remains just a hope; we’ve only tested the sound in rough prototype versions made of resin, with temporary driver anchoring. I’ll update this section in a few weeks when the finished product is in hand.Returning to the design, we spent entire days discussing and evaluating the functionality and aesthetics of the joint plate between the gimbal and the headband. We eventually found harmony, aligning the external bulk with the ear cup’s thickness, while curving the lower part to blend with the gimbal’s curvature. It took weeks to position the audio jack at a 40-degree angle so that when resting the headphones on a stand, the cable—if left attached—wouldn’t bend awkwardly at the base. There was simply no space inside the cup, and placing it outside would have been unsightly, yet the 20 mm needed for the jack had to come from somewhere. How I managed to fit that 20 mm jack into just 6×6 mm of protruding scrollwork is hard to explain, but that challenge was overcome too, and the scrollwork is now beautifully integrated into the whole structure.

I have a deep appreciation for beauty, but I don’t consider myself a capable designer. When I work on a project, I let the end goal guide me, allowing ideas to form along the way. In this case, however, I placed my complete trust in the aesthetic expertise of my friend Benny, who gave me the initial creative direction. Despite some deviations, where his taste clashed with functionality, I managed to preserve the original concept. The honeycomb grille and the exposed bolts were his ideas—both perfectly suited for the design. Leaving the bolts visible allowed me to develop the best possible solution for anchoring the driver. I needed precisely that type of bolting to keep the cup’s size within acceptable limits; I feared exceeding 120 mm in diameter but managed to contain it within 105 mm at the smaller end and 113 mm at the larger.While the original design sketched circular ear cups, the project’s evolution demanded oval ones, which we didn’t want. I compromised by subtly ovalizing the circle just enough to serve the design’s effectiveness. The result was fully approved by my friends who supported me, and I take this opportunity to thank Benny, Valentino, Mauro, and Achille for their financial contributions that lowered the production cost. My great reward lies in delivering them a high-end headphone, capable of competing with top-tier models, at actual production cost. As I write, it remains just a hope; we’ve only tested the sound in rough prototype versions made of resin, with temporary driver anchoring. I’ll update this section in a few weeks when the finished product is in hand.Returning to the design, we spent entire days discussing and evaluating the functionality and aesthetics of the joint plate between the gimbal and the headband. We eventually found harmony, aligning the external bulk with the ear cup’s thickness, while curving the lower part to blend with the gimbal’s curvature. It took weeks to position the audio jack at a 40-degree angle so that when resting the headphones on a stand, the cable—if left attached—wouldn’t bend awkwardly at the base. There was simply no space inside the cup, and placing it outside would have been unsightly, yet the 20 mm needed for the jack had to come from somewhere. How I managed to fit that 20 mm jack into just 6×6 mm of protruding scrollwork is hard to explain, but that challenge was overcome too, and the scrollwork is now beautifully integrated into the whole structure.

Another difficulty came from the fact that no ordinary milling machine could shape that form. I eventually found a specialized workshop with 5-axis milling machines. Compared to my previous projects, I also redesigned the headband, eliminating the bulk and aesthetic weight of a solid bar by introducing two large slots separating the ends—an elegant solution currently trending. Special attention was paid to the aesthetics and prestige of the headband padding. In addition to comfort, I chose fine leathers and Alcantara, with colors and contrasts carefully matching the chosen headphone finishes, available in total black, silver, and gold versions.

I know the world of headphones and the offerings of various companies, and I must admit that some models in production are truly beautiful and well-constructed, to the point that I wish I had designed them myself. But this headphone expresses the pinnacle of my current capabilities; I’ve loved it since the first prototype, and I can’t wait to have the finished version in hand, to share it with my friends, and above all, to enjoy the music it will bring. If I were to assign a score—admittedly biased—I’d give the headphones at least a 7, and my effort a 10 with honors. Whatever happens, it’s already a success

An obsessive pursuit of lightweight records? No!

I have observed with curiosity the recent trend among audiophile headphone manufacturers to compete for the lightest possible design, and I must admit that my curiosity remains unsatisfied. I am merely a humble designer, not a scientist, and by nature, I adhere strictly to the boundaries imposed by physics and mechanics. I am not the one to challenge those laws. If I had intended to build a lightweight headphone, I would have chosen lightweight drivers. However, a 100mm driver can only be lightweight if it uses fewer, less powerful magnets—and compromising on magnet size or strength is not an option for me, as they are responsible for generating the sound.

I have observed with curiosity the recent trend among audiophile headphone manufacturers to compete for the lightest possible design, and I must admit that my curiosity remains unsatisfied. I am merely a humble designer, not a scientist, and by nature, I adhere strictly to the boundaries imposed by physics and mechanics. I am not the one to challenge those laws. If I had intended to build a lightweight headphone, I would have chosen lightweight drivers. However, a 100mm driver can only be lightweight if it uses fewer, less powerful magnets—and compromising on magnet size or strength is not an option for me, as they are responsible for generating the sound.

The driver I’ve chosen is exceptional not only because of its gold diaphragm, but also because it is driven by 20 neodymium magnets, each weighing between 3 and 4 grams. When you sum this up with the rest of the driver’s structure, each unit weighs 120 grams, meaning a total of 240 grams for the drivers alone. This substantial mass requires proportional damping, necessitating a material structure at least double that of a typical 50-70 gram driver. While some sound engineers might argue otherwise, I rely on the mechanical laws I know: 2mm of damping surface thickness provides twice the vibration absorption of 1mm, and 4mm quadruples it. Each millimeter of thickness in the driver’s mounting base adds approximately 25 grams to the weight of each cup. The Dynamat, fully covering the upper and lower circumferences, adds another 14 grams. The driver is firmly sandwiched between six functional (and not just decorative) steel bolts, each adding 6 grams.

Am I trying to build a headphone that adheres to the laws of mechanics while also setting a record for lightness? Absolutely not. This headphone must be built this way. I’ve lightened all non-functional parts extensively: I created large internal cutouts in the cups where they wouldn’t interfere with the driver, reduced weight from the gimbals with aesthetic slots, and removed unnecessary steel from the center of the headband. But I didn’t spare a single gram or square millimeter in the functional components. I needed a comfortable headband, which cost me 50 grams, and I spent them. Steel was needed in the headband and the bolts, and I used it. Heavy Dynamat was required for the driver coupling, and I didn’t cut corners.

Even with all these choices, the headphone’s final weight is approximately 730 grams, which I consider a success given the complete absence of compromises aimed at reducing weight and the lack of any plastic components. This is an all-metal headphone. Perhaps not everyone will be able to wear it for long periods, but before jumping to conclusions, I would ask them to consider the extraordinary comfort that the proper weight distribution and the correct clamp provide. During testing, I personally used the headphone for many uninterrupted hours without experiencing any auditory or muscular fatigue.

In the end, my design philosophy mirrors that of those who created the Genesis 1.2 speakers. The designer simply built the speaker as it needed to be built, without concern for whether it would fit easily into homes. If I could have built these headphones in marble, I would have, because it would dampen even better. But staying grounded in reality, I believe the right choices were made regarding the final weight. It is the weight required by a driver of this size, with its heavy and powerful magnets. As I’ve stated before, my ambition is to build things correctly, respecting the laws of mechanics

Designing and constructing is my passion. In everything I create, nothing exists in isolation; functionality will always take precedence over aesthetics. However, I strive to harmonize the two whenever possible, for there is nothing more exquisite than that which is both beautiful and functional

I am an avid Hi-Fi enthusiast with design and construction skills; I understand materials, their properties, and their processing. However, I am not a manufacturer and I have no interest in selling my headphones except for a very limited number typically reserved for friends, which allows me to slightly reduce production costs for mutual benefit, without any monetary profit. I have many audiophile friends who generously offer their advice, which I consistently apply to my creations.

My headphones are entirely handmade, designed, and crafted by me, although I outsource the machining of my designed components to specialized workshops, as I do not have a lathe or CNC mill at home. I utilize a 3D printer to create the hundreds of prototypes necessary to achieve the final result.

My headphones are entirely handmade, designed, and crafted by me, although I outsource the machining of my designed components to specialized workshops, as I do not have a lathe or CNC mill at home. I utilize a 3D printer to create the hundreds of prototypes necessary to achieve the final result.

When evaluating the final product, friends and family often ask why I don’t want to sell my headphones, and the answer is always the same: “I don’t know, but I know that selling does not appeal to me. To sell, one must necessarily discuss money and I never talk about money. I would have to convince others of the quality of my work but I have no interest in doing so”

Therefore, the purpose of this website is not for selling but to keep track of my projects and share their contents with those who are interested

My heartfelt thanks go to my dear friends

❤️Graziano

❤️Benny

❤️Valentino

❤️Mauro

❤️Achille

for showing me their unwavering trust